Birding and Birdwatching Festivals and Events in 2021

From coast to coast and from Mexico to Canada, 2021 is filled with exciting birding festivals and events. We have compiled all that we could find for the year in the hopes that you can find an event near you to attend. Happy birding!

January 2021

February 2021

March 2021

April 2021

May 2021

June 2021

July 2021

August 2021

September 2021

October 2021

November 2021

December 2021

JANUARY 2021

Virtual Festival Of Birds

January 1 – January 31, 2021

Online

Join Rookery Bay and partners in January for a month of online activities, expert speakers and virtual adventures for nature and bird lovers everywhere!

Tracking Whimbrel: Journey With These Shorebirds On Their Non-Stop Flight From Cape Cod To South America

January 14, 2021 @ 12:00 pm – 1:00 pm Free

Online

From July through late September, Whimbrels migrate southward from their sub-Arctic tundra breeding grounds to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. While on the Cape, this large shorebird spends up to several weeks in the saltmarshes feeding on fiddler crabs—an important staple of their diet. After replenishing their energy reserves, building fat reserves and flight muscles, these Whimbrels will make a non-stop, trans-oceanic flight to their wintering grounds in the Caribbean Islands or all the way to the north coast of South America. Join us for a webinar on Thursday, January 14, with Manomet’s Alan Kneidel and Brad Winn, Mark Faherty, staff Biologist with Mass Audubon’s Wellfleet Sanctuary, and Dr. Sandra Giner, professor at the Central University of Venezuela, to learn what our innovative satellite-tracking research has uncovered about Whimbrel and other shorebirds.

Morro Bay Winter Bird Festival

January 14 – January 17, 2021

Morro Bay, CA

Morro Bay is a Globally Important Bird Area, located halfway between Los Angeles and San Francisco on the Pacific Flyway. Over 200 bird species have been seen during the festival weekend! The festival includes keynotes, field trips, workshops, bazaar, and family day. Saturday and Sunday keynotes to be announced.

Everglades Birding Festival – Cancelled

January 14 – January 18, 2021

Davie, FL

COVID-Safe Wings Over Willcox Birding & Nature Festival

January 15 – January 16, 2021

Online, Cochise Lake and Whitewater Draw Wildlife Area, AZ

From the rugged peaks of the Dos Cabezas and Chiricahua Mountains to the Dragoon Mountains, stretches the Sulphur Springs Valley, home to a great variety of plant and animal life. This bio-diverse area from grasslands to sky islands is home to a unique mix of flora and fauna and nearly 500 avian species. The Magic Circle of Cochise, which begins and ends in Willcox, offers the outdoor nature enthusiast the opportunity to experience some of the best birding and wildlife attractions in Southeastern Arizona.

26th Rains County Eagle Fest

January 16, 2021

Emory, TX

Rains County was recognized as the “Eagle Capital of Texas,” by the Texas Legislature in 1995 as part of an effort to protect and preserve the American Bald Eagle. Lake Fork, Lake Tawakoni, and the surrounding areas are nesting and feeding grounds for Bald Eagles and over 260 other bird species. The bus and barge tours to the lakes to see majestic Bald Eagles in their natural habitat are one of the main highlights of the festival. There will also be bird and animal exhibits and programs, animal encounters (including snakes), live entertainment and music, Aztec Dancers, vendors, food, educational speakers, and much more. Enjoy presentations from Last Chance Forever, the Blackland Prairie Raptor Center, Teaming With Wildlife, and others. Visit our website for more information.

Virtual Annual Tennessee Sandhill Crane Festival

January 16 – January 17, 2021

Online

As many as 12,000 cranes have overwintered at the confluence of the Tennessee and Hiwassee Rivers. Whether you’re an avid birder or you’ve never seen a Sandhill Crane before, the Tennessee Sandhill Crane Festival represents an extraordinary opportunity to witness a natural phenomenon that is truly unforgettable. Experience the migration of the Sandhill Cranes and many other waterfowl, eagles, White Pelicans, and Whooping Cranes.

Virtual For The Love Of Birds Festival

January 27 – January 29, 2021

Online

Learn from 14 of the coolest and most unconventional speakers, all from diverse backgrounds and experts in their fields, ready to help you expand what you thought was possible, learn practical skills, and fall even more deeply in love with the world of birds.

Teatown Hudson River EagleFest

January 30 – February 7, 2021

Ossining, NY

Teatown’s Hudson River EagleFest, the annual festival celebrating the bald eagle’s winter migration to the Hudson Valley, will kick off its 17th season on January 30, 2021, with a week of exciting virtual programs and limited in-person programs for children, families, and birding enthusiasts. Please visit our website for the most up-to-date information.

Eagle Watch Weekend

January 30 – 31, 2021

Oglesby, IL

The Eagle Watch Weekend features Birds of Prey Shows (Starved Rock Room) and family activities at Starved Rock Lodge (Great Hall), the Starved Rock State Park Visitor Center, and the Illinois Waterway Visitor Center. Take a short hike to the top of Starved Rock or Eagle Cliff and look for eagles in flight or join the park naturalist for a guided eagle viewing tour. Events run from 9 am to 4 pm each day.

FEBRUARY 2021

Virtual Spring Bird Camp

February 1 – March 18, 2021

Online

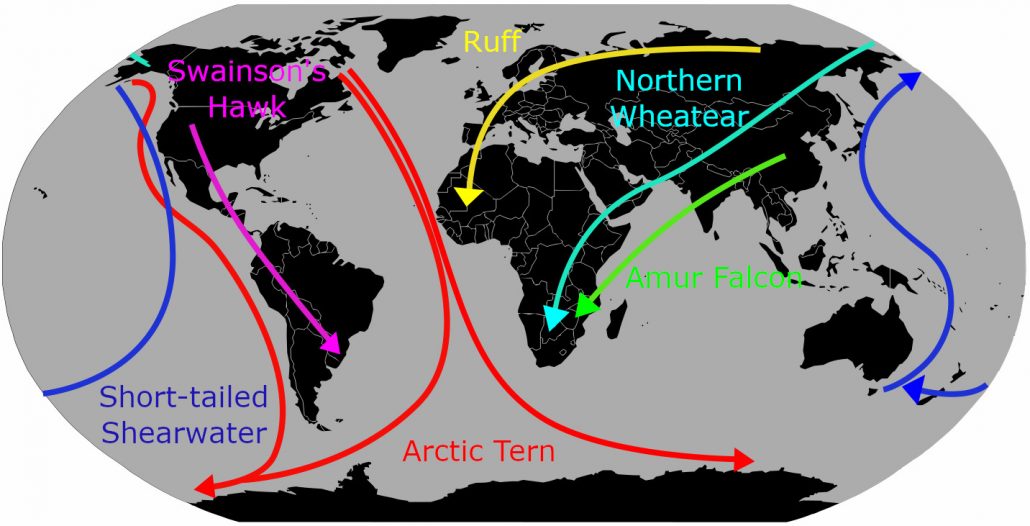

For this Spring Bird Camp, Environment for the Americas’ focus will be on how to separate male and female birds, understand the difference between bird calls and songs, and much more! With the spring migration of birds approaching, the curriculum will also include activities covering the importance of migratory birds.

19th Annual High Plains Snow Goose

February 4 – February 7, 2021

Lamar, Colorado

This one-of-a-kind festival is celebrating 19 years and is sponsored by the Lamar Chamber of Commerce, Colorado Parks and Wildlife, Kiowa County Economic Development, and Canyons and Plains. Join avid birders and historians for this three-day festival that offers amazing field trips, engaging speakers, and informative programs.

Galt Winter Bird Festival

February 6, 2021

Galt, CA

The 14th Annual Galt Winter Bird Festival advances public awareness of the conservation of the region’s wildlife. This area is a critical stop for many important species of birds commuting on a diverse chain of habitats called the Pacific Flyway. In addition to these magnificent migrating birds, hundreds of bird species call Galt and its surrounding cities home. The festival brings tours, vendors, programs, and presentations for guests to enjoy. There will be wildlife entertainment for all ages, art, food and more! Over 1,200 attendees enjoyed our last festival.

Cumberland County Winter Eagle Festival

February 6, 2021

Mauricetown, NJ

Cumberland County, New Jersey, has the largest number of nesting Bald Eagles in the state. The Winter Eagle Festival will feature speakers, viewing stations along the Delaware Bay and Maurice River, and guided trail hikes. The Eagle Festival is a partner effort between the County of Cumberland and numerous environmental organizations including the Cape May Bird Observatory, Audubon Society, Natural Lands, Association of New Jersey Environmental Commissions, American Littoral Society, Citizens United to Protect the Maurice River and it’s Tributaries, and many others.

Annual Winter Wings Festival – Cancelled

February 11 – February 14

Klamath Falls, OR

Sax-Zim Bog Winter Birding Festival

February 12 – February 14, 2021

Meadowlands, MN

The 14th Annual Sax-Zim Bog Winter Birding Festival will take place on February 12, 13, 14, 2021, in Meadowlands, Minnesota. Buses with guides will tour the Bog daily, beginning on Friday and ending on Sunday. Friday and Saturday Evening Program Speakers to be announced.

Virtual 3rd Annual Birds On The Niagara International Bird Festival: A Winter Virtual Celebration

February 12 – February 14, 2021

North Java, NY

Join us on Valentine’s Day weekend when many of Niagara’s bird species are in breeding plumage and are exhibiting courtship behavior. Birding on the Niagara River in Winter is as good as it gets. Up to 19 species of gulls, waterfowl, and winter irruptive birds use this area as winter habitat. 100,000 birds can be found along the Niagara River Corridor Globally Significant Bird Area on any given winter day.

Virtual Laredo Birding Festival

February 13, 2021

Online from Laredo, TX

The Laredo virtual Birding Festival includes high-quality birding videos of our most popular Laredo Birding Festival destinations. View stunning birds and landscapes of our South Texas region as we take you on an exclusive birding journey by boat, on historic ranches and local birding hot-spots!

Brunch With The Birds

February 13, 2021

Arlington, TX

Enjoy an introduction to birding for the whole family at Brunch with the Birds on February 13 at River Legacy Living Science Center! Register for guided hikes at 11 AM, 1 PM, and 3 PM where you will learn the basics of bird counting. Then enjoy free coffee and hot chocolate, breakfast snacks, informational demonstrations, and access to our new traveling exhibit! Masks required inside and on hikes. Must pre-register to attend.

Virtual/Hybrid San Diego Bird Festival

February 17 – February 21, 2021

Online and San Diego, CA

The San Diego Bird Festival is a celebration of the birds and habitats of San Diego County. Our 2021 festival will feature over 20 field trips reaching every corner in the county, plus workshops about destinations, identification tips, photography, and guest speakers.

Annual Whooping Crane Festival

February 25 – February 28, 2021

Port Aransas, TX

The Coastal Bend is the only spot in the United States where the endangered Whooping Crane can be viewed at close range, and the Port Aransas Chamber of Commerce celebrates this astonishing natural wonder with an annual festival honoring these grand birds. In addition to the Whooping Crane, an awesome array of wintering migratory birds flock into the wetlands and onto the Texas shorelines of Mustang Island in and around Port Aransas. Birding tours by land and sea are highlights during the festival.

16th Annual Eagle Expo

February 26 – February 27, 2021

Morgan City, LA

Eagle Expo includes boat tours into various waterways to view eagles, Birds of Prey program, presentations, speakers, fellowship, photography workshop, and Water & Nature Expo. Exhibits and vendors will have products that highlight outdoor recreation and our waterways.

MARCH 2021

Vallarta Bird And Nature Festival

March 5 – March 7, 2021

Puerto Vallarta, Mexico

Hosted by the Vallarta Botanical Gardens, the festival honors the amazing diversity of birds and nature that exist in Mexico and more specifically in the Puerto Vallarta area, Banderas Bay and Cabo Corrientes. This year we are fundraising in support of The Macaw Sanctuary with hopes to fund Military Macaw nestbox construction and installation. Guest speakers to be announced. Tours to bird-rich areas within an hour’s drive of the Vallarta Botanical Gardens will be offered each day along with tours of the beautiful and internationally recognized botanical gardens. Fun and educational children’s activities will be offered along with a family birding walk within the botanical gardens.

Crane Season

March 6 – April 11, 2021

Gibbon, NE

Every March, over a million Sandhill Cranes converge on the Platte River Valley in central Nebraska to fuel up before continuing north to their nesting grounds. Audubon’s Rowe Sanctuary is at the heart of this magnificent crane staging area. Rowe Sanctuary offers daily guided tours at sunrise and sunset to view the spectacular concentrations of Sandhill Cranes on their river roosts from new “discovery stations” strategically placed along the Platte River close to Sandhill Crane roosts.

Cape Ann Winter Birding Boat Trip

March 6, 2021

Gloucester, MA

Birdwatchers from New England and beyond flock to Cape Ann to participate in the Cape Ann Winter Birding Weekend each year. Weather permitting, we are hosting the Winter Birding Boat Trip, aboard the PRIVATEER IV, with 7 Seas Whale Watch. Saturday, March 6, 2020, from 8 am to 1 pm.

Annual NatureFest

March 6, 2021

Humble, TX

Nature lovers of all ages are invited to our Annual NatureFest introducing visitors to local environmental organizations, outdoor activities, and native plants and wildlife. This free family event includes pontoon boat tours, guided walks, live animals, a catch-and-release fish tank, and a variety of presentations throughout the day.

Virtual Migratory Bird Fest And Birdathon

March 12 – March 31, 2021

Online

Migratory Bird Fest is a community festival usually held at Mitchell Lake Audubon Center in May to celebrate spring migration. Mitchell Lake Audubon Center cancelled the festival in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Virtual Migratory Bird Fest is our way of holding the festival for the community in a socially distant and safe way.

Virtual Monte Vista Crane Festival

March 12, 2021

Online

The bus tours and large gathering have been canceled for the 2021 Crane Festival. Instead, from the comfort of your own home join us for beautiful videos, images, and interviews featuring twenty thousand Sandhill Cranes and the landscape of the San Luis Valley, Colorado. Our feature presentations are “Cranes of the World” by crane naturalist Sandra Noll and a spectacular slide show by professional photographer Ed MacKerrow. Included are short video productions about cranes, San Luis Valley water issues, and short interviews with refuge staff and local community members.

Virtual Wings Over Water Northwest Birding Festival

March 19 – March 21, 2021

Online

Wings Over Water 2021 Northwest Birding Festival Has Gone Virtual And Will Take Place On March 19, 20, 21 With Live Webinars, Video Bird Walks, Kids’ Activities And More To Enhance Your Outdoor Experience And Love Of Birding. Join us in-person in 2022 for a birding adventure along the coastal areas of Blaine, Birch Bay, and Semiahmoo in the northwest corner of Washington State.

Tundra Swan Festival

March 20, 2021

Cusick, WA

The festival is an annual, one-day event all about the Tundra Swan migration! The swans historically favor the Pend Oreille River Valley as they journey to ancestral breeding grounds on the Arctic tundra. A medium distance migrant, the Cygnus columbianus may travel from as far away as New Mexico, the California coast, and Colorado River, or as near as southern Idaho. Whatever the distance, they are a welcome sight and sound; a herald of spring. The event is co-hosted by the Natural Resources Department of the Kalispel Tribe of Indians and the Pend Oreille Region Tourism Alliance (PORTA).

Virtual Wings And Wetlands Birding Festival

March 24 – March 26, 2021

Online

Join Us For the 2021 Virtual Wings & Wetlands Festival. Explore birds, wetlands, and conservation messages through presentations by renowned experts, interactive socials, and on-demand web resources. The 2021 Wings and Wetlands Festival features renowned experts. These experts will walk you through topics of bird watching, identification techniques, Kansas wetlands, and conservation.

Space Coast Virtual Photography Experience

March 26 – March 28, 2021

Online

Learn from the pros: presentations, panel discussions, tools, and techniques over 3 days with 20 speakers in 7 categories. The Space Coast Virtual Photography Experience is offered at several levels so you can choose the categories or talks to inspire your photography and take you to higher levels of skill. PLUS . . . presentations will be recorded and the replays available until April 30, 2021.

APRIL 2021

Annual Great Louisiana BirdFest

April 1 – April 5, 2021

Mandeville, LA

Birders travel from all corners of the U.S. and from around the world to participate in the Great Louisiana BirdFest. Our area is a prime bird-watching location, and the Great Louisiana BirdFest is considered one of the premier birding events in the country. Join us and enjoy what people travel long distances to see and experience “the ideal spring weather, natural resources, and wildlife of Southeast Louisiana” in our own backyard. Birding trips by foot and pontoon boat for expert and beginning birdwatchers in varied habitat, including swamps, wetlands, pine savanna, and hardwoods. Photography and other workshops, Southern food and hospitality.

A Celebration Of Swans

April 1 – April 30, 2021

Marsh Lake, Yukon Canada

Yukon’s premier birding festival brings residents and visitors alike out to great swan viewing areas to welcome spring to the North. The mass migration of tens of thousands of swans, ducks, and geese is not to be missed. The Swan Haven Interpretive Centre, open daily in April, is the hub of the festival. Events include photography and art workshops, presentations, campfire storytelling, children’s activities, and more.

Spring Fling

April 3 – May 2, 2021

Quintana, TX

Twice each year millions of birds swarm across the Americas, traveling thousands of miles as they migrate between breeding and wintering grounds, stopping in route to refuel at coastal stopover sites. Spring Fling is an amazing opportunity to see migratory songbirds as they arrive at stopover habitat along the coast. This is great time to enjoy the wide variety of species that migrate through Texas, such as orioles, grosbeaks, tanagers, and numerous warbler species, to name just a few. We will have knowledgeable volunteers and staff on hand at Quintana to answer your questions, keep a daily list, and sell water, snacks, and field guides. Even if you don’t know a cardinal from a blue jay, you will enjoy a trip to Quintana to witness the diversity and abundance of migrating species.

Attwater’s Prairie Chicken Festival

April 10 – 11, 2021

Eagle Lake, TX

Come see the endangered Attwater’s prairie-chickens dance in their native habitat! Early morning van tours will take participants up to one of the booming grounds to watch the male prairie chicken’s famous courtship dance. Other events this weekend include native plant guided tours, bird walks with experienced birders, Native American dance presentations, refuge van tours, and a merchandise booth sponsored by the Friends of Attwater Prairie Chicken Refuge.

Virtual Wisconsin Prairie Chicken Festival

April 12 – April 17, 2021

Online

Every April, the Greater Prairie-Chicken dances at dawn, and typically people can assist researchers by sitting in a blind to watch, and log, the mating of this unique Wisconsin species. Due to COVID, the 2021 Wisconsin Prairie Chicken Festival (WPCF) is going to be a virtual, online experience. The event is free, but spots may be limited, so registration is required.

Annual Migration Celebration

April 13 – May 8, 2021

Brazoria, TX

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, the traditional Migration Celebration (MC) held at San Bernard NWR will not be offered this year. In its place we are sponsoring a series of Saturday activities at five different venues: Family-friendly outdoor activities are being planned for each venue. Each event will be held from 10AM to 4PM. We will post activity updates on our website and on the Migration Celebration Facebook page.

AWE Virtual Talk With Scott Weidensaul

April 13, 2021 @ 5:30 pm EDT

Online

An epic reflection on what we’re learning about the greatest natural phenomenon on the planet—and what we must do to preserve it.

Olympic Birdfest

April 15 – April 18, 2021

Sequim, WA

This festival provides participants the opportunity to view a wide variety of birds normally seen on the Olympic Peninsula. Field trips are planned for Sequim Bay, Port Angeles Harbor, Ediz Hook, Dungeness Spit, the Elwha River and at Neah Bay, as well as trips through wooded areas to view songbirds and locate owls in the evening. Boat trips to Protection Island are also planned. The North Olympic Peninsula is widely known as a great place for bird watching. The day of the Olympic BirdFest is timed to overlap wintering birds and the beginning of spring migration.

In addition to the field trips, birders may participate in presentations, workshops and a banquet. A tour explaining the Jamestown S’Klallam tribal totem poles at the Tribal Center and the Seven Cedars Casino will also be offered.

19th Annual Galveston FeatherFest Birding & Nature Photography Festival

April 15 – April 18, 2021

Galveston Island, TX

FeatherFest is the Island’s annual birding and nature photography festival held during the height of spring migration. Galveston is one of the top locations in the country for birding because it hosts a wide variety of habitats in a small geographical area where some 300 species make their permanent or temporary home.

Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival

April 16 – April 18, 2021

Grand Isle, LA

The best spring migration birding across the southeastern United States, the Grand Isle Migratory Bird Festival offers guided birding tours from Elmer’s Island, The Nature Conservancy’s Maritime Forest and Birding Trail to the Grand Isle State Park. Grand Isle is an essential stop for migrating songbirds after their long flight across the Gulf of Mexico during spring migration. The island has become one of the best places in the world to see the variety of species during spring and fall migration. The Migratory Bird Festival not only celebrates their spring arrival but also provides easy viewing access to visitors.

Virtual Godwit Days Spring Migration Bird Festival

April 16 – April 18, 2021

Online

The Godwit Days Spring Migration Birding Festival will be offering a free, virtual, three-day program April 16 through 18. It will highlight some favorite species and the spots where they occur. Most sessions will be 60 to 90 minutes in length, with breaks in between. Some will be live-streamed (and also recorded for future viewing), and others will be pre-recorded and posted online. Participants will be asked to make donations to keep the festival going, both this year and beyond.

11th Pannonian BirdExperience

April 17 – April 25, 2021

Illmitz, Austria

Since 2010 Austria’s birdiest Nationalpark Neusiedler See – Seewinkel hosts the Pannonian BirdExperience annually in April. This event includes a three-day trade show for bird watching—everything you need and all you want to know can be found here at numerous stands: optics and cameras, including accessories, functional clothing, nature tours, books, Nature Reserves, and National Parks, as well as bird- and nature-conservation organizations. The 9-day program with field trips, workshops, and lectures starts the weekend before and makes the visit to the Pannonian BirdExperience an incomparable experience!

Georgia Bird Fest

April 17 – May 16, 2021

Atlanta, GA

Birds, y’all! Georgia Bird Fest celebrates spring migration in the southeastern U.S. with 40+ field trips, weekend trips, workshops, and keynote speakers, both virtually and in-person across the state. Keynote speakers for 2021 include Scott Weidensaul (April 18) and Carolyn Finney, Ph.D. (May 16).

Birdiest Festival In America

April 21 – April 25, 2021

Corpus Christi, TX

Corpus Christi’s BIRDIEST FESTIVAL IN AMERICA has earned its wings, bringing birders of all levels to the Texas Gulf Coast to experience amazing spring migration in perhaps the busiest flyway in the country! Based at South Texas Botanical Gardens & Nature Center, the 2020 festival (before cancellation) had doubled its 2019 registration! Now larger and longer, 2021 features 14 different field trips to famous South Texas ranch and coastal hot spots! Eight different presentations and workshops; three bird walks; and nine Jonathan Wood “Raptor Project” shows also are offered.

Florida’s Birding & Photo Fest

April 21 – April 25, 2021

St. Augustine Beach, FL

Florida’s Historic Coast will present another great year of birding and outdoor photography. There will be more than 130 exciting photography and birding events, including field workshops, classroom sessions, as well as night and action photography. Festival participants will benefit from insights and instruction from a collection of upper echelon international nature and wildlife photographers — a group that continues to solidify Florida’s Birding & Photo Fest as one of the premier events in North America.

Point Reyes Birding And Nature Festival

April 22 – April 25, 2021

Point Reyes Station, CA

Save the date for the Point Reyes Birding and Nature Festival! This three-day event is a program of the Environmental Action Committee of West Marin (EAC) and allows attendees to experience one of the most ecologically significant areas along the Pacific Coast with experienced naturalists and biologists. Just outside the magnificent Point Reyes National Seashore, participants will enjoy the biological diversity of plants and animals of this area and the surrounding regional habitats of the rural landscapes of West Marin County. The Festival takes place at the height of spring migration with opportunities for over 184 bird species! Over 50 field events and indoor workshops focused on a variety birds, habitat, plants, and mammals.

Virtual Verde Valley Birding And Nature Festival

April 22 – April 25, 2021

Online from the Verde Valley, AZ

Friends of the Verde River will host the annual Verde Valley Birding and Nature Festival in a unique new way, bringing the natural treasures and incredible birding of the Verde Valley directly to your home. Join us for the Virtual Package, which includes all festival webinars and opportunities to connect with professional presenters. Engage with other bird lovers and learn about the amazing beauty and biodiversity of the Verde River, one of the last free-flowing rivers in the Southwest. There will be a limited number of small, in-person birding tours offered within the state of Arizona. This accessible and beloved festival is perfect for nature lovers, lifelong learners, and all levels of birders.

Spring Chirp

April 22 – April 25, 2021

Weslaco, TX

Perfect for those seeking a superior introduction to birding South Texas, our small-group field trips with expert guides to hotspots and super-premium destinations make this the best way to see a wide variety of specialty birds and migrants at prime time for hawk migration.

Virtual Harney County Migratory Bird Festival

April 22 – April 25, 2021

Online

Each April thousands of migratory birds rest and feed in the open spaces of Oregon’s Harney Basin of Southeast Oregon. Although we cannot meet in person this year for his spectacular experience, we are working diligently and creatively to put together a VIRTUAL EVENT that will be FANTASTIC.

Red Cliffs Bird Fest At Greater Zion

April 22 – April 24, 2021

St. George, UT

The 2021 Red Cliffs Bird Fest will showcase the birding habitat of Greater Zion during spring migration where the beauty of the birds is truly matched by the beauty of the scenery. Field trips will combine birding with other outdoor activities for maximum enjoyment. Join us as we spend 3 days exploring the varied birding habitats throughout incredible Southwest Utah! Within one day, you can experience the birds of micro-wetlands, low deserts, riparian habitats, and the aspen-fir belt. This year’s field trips will offer access to all these ranges including guided trips in Zion National Park and the famous Lytle Ranch Preserve!

Owens Lake Bird Festival

April 23 – April 25, 2021

Lone Pine, CA

Details Of The 2021 Owens Lake Bird Festival Are Still Pending As Organizers Monitor The Situation And Follow Guidelines Set By Local And State Health Officials To Ensure The Safety Of Our Community. The Owens Lake Bird Festival showcases the migration of birds through the Mojave desert, along the historic Owens Lake. This festival merges magic of historic western movie scenes and ancient tribal histories at the Alabama Hills with the stark natural beauty of Death Valley’s doorstep. 30+ outings highlighting the birds, photography, botany, geology, and history of this important location. LADWP’s unique dust management engineering restored the lakes important bird habitats where saltwater and freshwater interact to host a huge number of traveling bird species.

Hatchie BirdFest

April 23 – April 25, 2021

Brownsville, TN

Unique outdoor adventures and over 200 species of birds await you on the Hatchie National Wildlife Refuge. Events will include speakers and demonstrations, hikes, canoeing, and exhibitors. Entertainment by The Dirt Pilgrims folk band. Perfect for seasoned birders or beginners.

Willis Point Bluebird Festival

April 25, 2021

Willis Point, TX

The W. P. Bluebird Festival Association, Inc. (501(c)3 nonprofit) has hosted the annual Bluebird Festival in the spring of each year since 1994. In 1995, Willis Point was named Bluebird Capitol of Texas by Governor George W. Bush. The festival is held in downtown Willis Point, Texas, on 5th Street, from 8 am until 5 pm. Events include Bluebird Tours and Train Depot, Car Show, Lil Miss Bluebird Pageant, Chili Cook-off, and Kidz Zone.

New River Birding & Nature Festival

April 26 – May 1, 2021

Opossum Creek Retreat, WV

The annual New River Birding & Nature Festival takes place in and around the New River Gorge National River in the heart of the upland, hardwood forests that Cornell Lab of Ornithology identified as a crucial stopover habitat for the continued survival of species, such as Golden-winged, Blue-winged, and Swainson’s Warblers, as well as the Scarlet Tanager. Our bird and nature watching festival highlights more than 100 bird species on a variety of daily birding tours.

Stikine River Birding Festival

April 29 – May 2, 2021

Wrangell, AK

Stikine River Delta has the largest springtime concentration in North America of thousands of Bald Eagles. The festival is the perfect opportunity for adventurous birdwatchers to also observe millions of shorebirds, which migrate to the delta each spring. The Stikine River and its tributaries are located within the Stikine-LeConte Wilderness Area of the Tongass National Forest. Wrangell Stikine River Birding Festival celebrates the spring migration of Bald Eagles, Snow Geese, Sandhill Cranes, and thousands of shorebirds. Events for all ages, including art and photo contests, build a feeder, guest speakers, and of course—an opportunity to explore the surrounding islands and Stikine River flats for birds!

Birding The Border

April 29 – May 2, 2021

Del Rio, TX

Birding the Border takes place each spring in Val Verde and Kinney counties, Texas! This puts us in the middle of the Central Flyway and at the intersection of 3 different eco-regions, providing our participants with the opportunity to see a wide variety of birds in the borderlands of southwest Texas. Participants have access to private ranches, some of which have never been birded, and other restricted-access sites. This is a unique Texas birding experience that includes tours led by professional guides, educational programs, a trade show, and so much more.

Tofino Shorebird Festival

April 30 – May 2, 2021

Tofino, BC, Canada

The Tofino Shorebird Festival celebrates the spring migration of shorebirds with a series of educational birding activities throughout the Tofino region. We draw on local and visiting experts to participate in the festival, offering guest lectures, birding workshops, boat trips, and much more! This is a great opportunity to experience the largest wildlife migration in the region, learn about these impressive birds, and understand why Tofino is one of the very best places in western Canada for bird watching.

Little St. Simons Island Spring Birding Days

April 30 – May 7, 2021

St Simons Island, GA

Celebrate spring migration on Little St. Simons Island! Guest ornithologists join our staff naturalists on excursions highlighting the abundance of species that flock here during this special time. Three-, four-, and seven-night packages, priced per couple, double-occupancy. Package rates include lodging, three meals daily prepared by our chefs, soft drinks, all island activities including guided naturalist excursions and use of recreation gear as well as boat transfers to and from the island.

MAY 2021

Red Slough Birding Convention

May 1 – May 4, 2021

Idabel, OK

The Annual Red Slough Birding Convention in Southeast Oklahoma will take you to several birding hotspots (Red Slough, Little River NWR, and McCurtain County Wilderness Area) to see species, such as Purple Gallinule, White Ibis, Black-bellied Whistling-Duck, Least Bittern, Painted Bunting, Swainson’s Warbler, Scarlet Tanager, Brown-headed Nuthatch, Baltimore Oriole, Red-cockaded Woodpecker, and many other neotropical migrants, shorebirds, and wading birds. Tours will also showcase the diverse dragonflies, wildflowers, and champion trees (Prairie Wildflowers, Red Slough Dragonfly Tour, and Champion Tree Tour).

JUNE 2021

JULY 2021

AUGUST 2021

SEPTEMBER 2021

OCTOBER 2021

NOVEMBER 2021

DECEMBER 2021